S2 E11 - How do I help my students who aren't blending?

00:00:00

Introduction.

Well, hello. Hello. It's Jocelyn here. Welcome to the Structured Literacy Podcast. The place where we discuss everything about structured literacy and the complexity of making it happen in our schools and classrooms. I'd like to begin by paying my respects to the Palawa people of Tasmania and particularly the people of Padaway Burnie, where this episode is recorded.

00:02:25

Today's topic - Questions from our Facebook Group.

In this episode, I'm doing something a little different. Rather than bringing you just one topic, I'm going to share answers to some questions that have been asked inside the On the Structured Literacy Bus Facebook group over the past couple of months. When one person asks a question, you can bet your bottom dollar that others will benefit from the answers. So, let's dive in.

00:02:37

Question 1 - Chunking.

Our first question comes from Margaret.

Hi, Jocelyn. I'm wondering if there is any evidence or best practice on using chunking when reading. For example, I have a few students who are struggling to blend, even with continuous blending strategies. I also have some students ready for multisyllabic words. In both situations, by the time they have sounded out each sound, they've lost some sounds. Jump becomes /ump/, or /st/ /u/ /ck/ becomes /tuck/. The students, ready for multisyllabic words, struggle to put it all together. Should I be teaching /j/ /u/ /mp/, /j/ /ump/, /jum/ /p/, jump? Thank you, Margaret, for this question.

There are a few layers to unpack this particular one, and I don't want to assume that anyone has experience in any of it, so I'll start by giving background to the issue to put the answer in context.

In previous instruction, we used to teach blends, also known as consonant clusters and rimes, <r> <i> <m> <e> <s>, which also happens to be the part of the word that rhyme, <r> <h> <y> <m> <e> in the list, fat, bat, cat, sat, mat. The first part of the word that is replaced as we work our way through that list is called the onset. Words with the same rime, <r> <i> <m> <e>, can be called a word family. So children were taught the basic code in a bit of a loosey goosey fashion and were given blends and rimes to learn as units. That is, blends and rimes were presented on flashcards for students to learn in the same way that we used to teach sight words. They were then given words to read, assuming that if they used these in practice, they would learn to blend more easily than if they dealt with the individual graphemes. These practices aren't supported, as introducing blends and word families adds hundreds of new bits of information to the content that students need to learn. It's also not reflective of the evidence about how blending and smooth, fluent reading develops. It's much better to teach students to blend than to teach them blends and rimes as units.

To understand the relationship between this previous practice and current reading science, we need to know about the process of orthographic mapping. Many of us have heard this term and know that it relates to embedding words into long term memory, but we haven't perhaps learned that orthographic mapping is a cognitive process that happens in phases, not in one quick step. The process of orthographic mapping has been outlined for us by Linnea Ehri, a researcher from the US. I had the great pleasure of spending time with Linnea Ehri in 2022 and presenting alongside her at an event. And to say that I was fangirling is a complete understatement.

Professor Ehri's (2014) theory of orthographic mapping presents four phases of learning to read. If you have a copy of my book, Reading Success in the Early Primary Years, you can find a more in depth explanation on page eight. The first phase is called the pre alphabetic phase, where children don't think about the phoneme-grapheme correspondences at all. The second phase is where students pay attention to just some correspondences in a word. This is called the partial alphabetic phase. Children grab onto a couple of letters in the word and then connect that with the whole word. The third phase is where the secret sauce is. It's the full alphabetic phase where students attend to all correspondences in a word. The research indicates that through repeated practice, sounding out words sound by sound, the words move into long-term memory, and students begin to move to the fourth phase, the consolidated phase. In the consolidated phase, The brain learns to recognise larger units, such as consonant clusters, rimes and syllables and then uses them to lift words from the page with ease. To add to this, Stanislas Dehaene (2009) describes how students move from left to right blending to simultaneous or concurrent blending, where all correspondences are dealt with at the same time, and that's the difference between a student who's learning to read and one who has learned. The student who's learning to read reads left to right, one sound at a time. People like us who are proficient readers are still dealing with the correspondences and the units, but we just do it all at once.

Margaret's question is one that will relate to so many of our listeners. She's asking what to do when children simply don't arrive at that concurrent or simultaneous blending in the first place because their wobbly memories mean that by the time they've reached the end of the word, they've forgotten what was at the start, and they can't get the words off the page. It's clear from Margaret's question that the students are able to blend with three phonemes. She describes that jump becomes /ump/. So the three phoneme blending is happening for Margaret's students. Now, I want to preface my response to this question by saying that the vast majority of students will learn to blend using the process of repeated practice, reading all through the word, first with CVC words, and then four and five phonemes. They won't need anything special. So please, please, please don't take what I'm about to say and think that you have to be applying this to your whole class. If you are doing something else right now, if you're multitasking, come back to me because I'm going to say this again. What I'm about to say is not for your whole class, but it is a consideration for students who are not making progress in blending, despite you providing robust instruction in phonics at the tier-one level, including word level blending and segmenting for a reasonable period of time and they have access to additional tier two support that gives them higher intensity opportunities with regular practice. It's only at that point when you've provided all of that, and the student still isn't making progress, that you can say that they need something different.

The child that Margaret describes sits in the tier-three space where individualized options for learning sit, and that's what they need. Something special, something different, something really intensive. Now, full disclosure, I'm not an expert in the tier-three space. So when Margaret asked this question, I turned to Kate Andrew from Read3 for support. Here is her response. I'm going to read to you from the message in the Facebook group.

Now, if you want to know more, everyone, you can visit read3.com.au, that's the website for Read3. So thank you so much to Kate for being a member of our group and helping us with these curly questions.

I know that there'll be some people listening to this episode and thinking, "Wow, Jocelyn? Are you serious? We have worked so hard to remove word families and blends from our classrooms, and you're encouraging people to bring them back in?" And I want to say that I get that reaction. I understand it completely, and it's one that I've had a few times about different things myself, where my response to a suggestion is quite heightened and maybe a bit of an overreaction because I've worked so hard to help people eliminate certain practices. But here's the thing, If we are going to move beyond the surface-level knowledge of reading instruction to make sure that every child in our classrooms learns to read, we have to start working with some of the nuances of practice.

In this particular case, no one has said to start flashing onsets and rimes at kids to learn those units. Nobody has said to move away from phoneme-grapheme correspondences. Those are still taught in the same way that you're teaching them to everyone else. What I think Kate's saying here is that to get children blending, we need to reduce the number of units they have to work with. So in the case of jump, the child isn't saying /j/, /u/, /m/, /p/ because that's where they're getting lost. They might have a little practice of /u/, /m/, /p/, /ump/. Now I wanted to tell you all that I have not done the Read3 training. So this is my interpretation of Kate's comment. You could have the student have a little practice of /ump/. /u/ /m/ /p/ /ump/, /u/ /m/ /p/ /ump/, /u/ /m/ /p/ /ump/ for a bit and then add the /j/ at the start. So now, instead of four phonemes, the child can say /j/ /ump/ /jump/. They haven't worked with that rhyme as a single unit, they've actually blended it, but you've done it a few times to give them a run-up. So when they get to jump, they only have two chunks or units to deal with. Before you start emailing me and saying that Linnea Ehri says that children need to blend all through the word, Kate and Robyn from Read3 spoke to Linnea Ehri at the Learning Difficulties Australia event last year, where I also presented. They described their process to her, and she said, "Of course, that makes so much sense. Not all children are going to develop smooth blending on their own, and they will need extra help."

Many children most children move from the full alphabetic phase to the consolidated phase with the repeated practice that you have in your classroom. But some of them are just going to need something different. Linnea Ehri then spoke with Kate and Robin about people she knows who work with students with reading difficulty and employ a similar method, and there are other people in the space who are also recognising that kids with extreme phonemic difficulties need something a little different. But I'm going to come back and say again, please don't think that this is how you do this for everyone. This is for your students who have not responded appropriately in their learning to the strong instruction you're providing.

In any decision of practice, it's not about something always being good or always being bad, but being able to answer the question, "Under what circumstances is this practice helpful?" What I'll also say is that this chunking method is a step on the way to full phonemic blending. It's a pit stop, if you like. It's the bridge. We don't end there for those students who are having difficulty with 'jump'. We introduce this other little way first, and then they will move into full phonemic blending, but they need something to help along the way. If you want to know more about supporting students who are simply not responding to Tier-1 and Tier-2, despite your school and you doing all those right things, you can visit Read3.com.au for support.

00:14:32

Question 2 - Dots and Dashes.

The next question is way quicker to answer and comes from Alicia B.

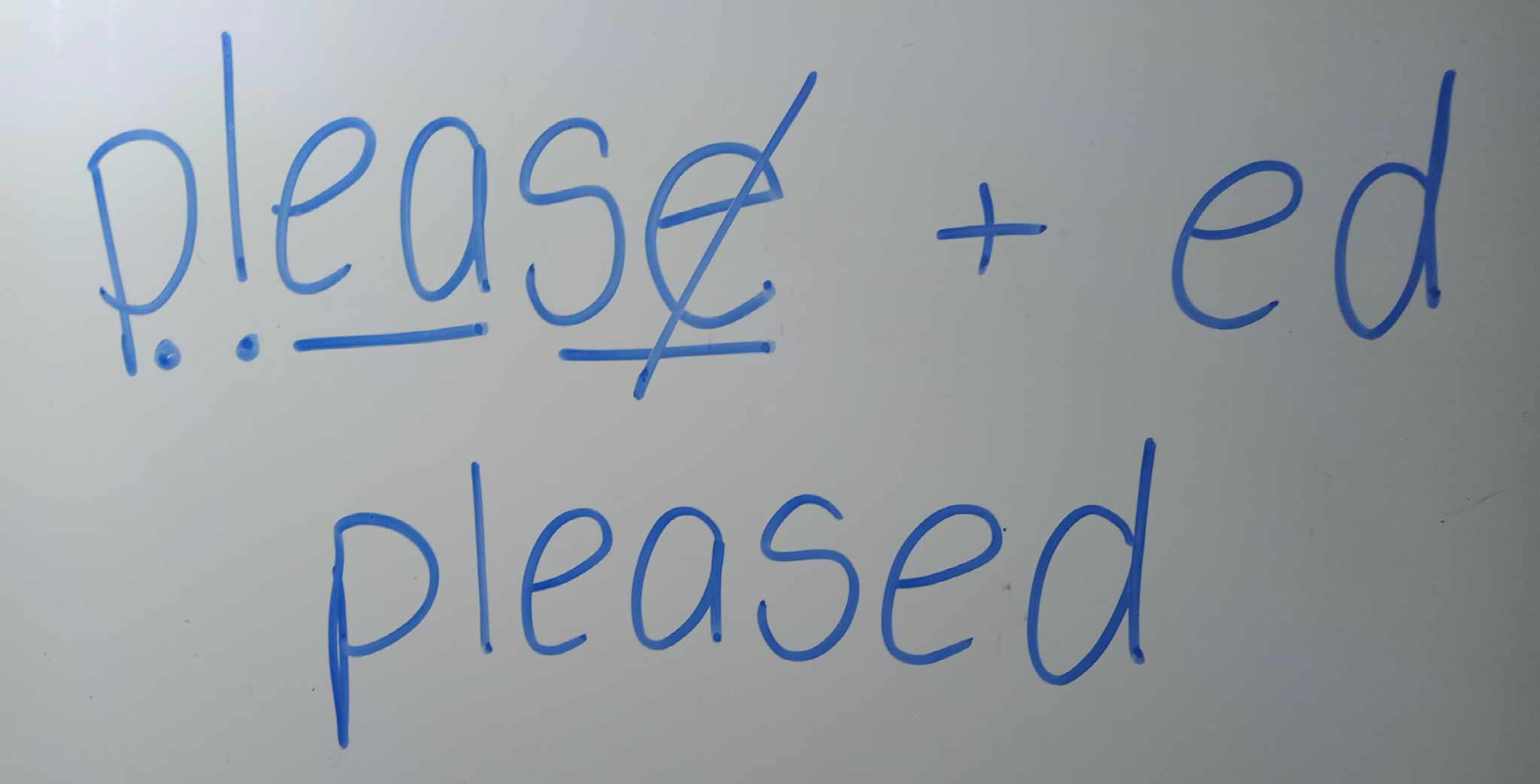

Can you please help me dot and dash the word pleased, as in "I was pleased that happened?" We had a few answers in our staff meeting.

For our listeners who might not be familiar with the dotting and dashing of words, I'll briefly explain what that means. A common practice is to make the phoneme-graphemes of a word visible by placing dots under single letters and lines under digraphs and trigraphs in words. I'm not a fan of presenting these marks on a slide for the students because I don't think that they're as meaningful to them as if we put the marks on live in front of them or even get the students to do it themselves once they're able, but that's neither here nor there in answering this question.

The answer to Alicia's question isn't as simple as putting dots here and dashes there. It's about how we help children understand how words work. Phonics, which the dots and dashes make visible, is just one layer of word construction. It works for many things, but, like phonics in general, has limitations. To really understand how the word pleased works, children need to know that the base please has had the past tense <ed> added to it to form a new word. They also need to know that when a vowel suffix is added to a word, we usually drop the <e> in the base word before adding the suffix. Unpacking this process for the students will be much more valuable than simply popping some dots and dashes on the board. So if I was helping students understand this word, I'd say the base of the word, pleased, is______ and I'd leave it open, and hopefully, the children say, 'please', and if they don't, I'd say it for them. We sound it out, /p/ /l/ /ea/ /se/, and I'd hold up one finger for each sound, /p/ /l/ /ea/ /se/, and apply the appropriate dots and dashes to the written word. I would then write a plus sign + after the base, please, and write the suffix ed, saying to turn please into pleased, we need to add the suffix <ed>, which shows that the word is past tense. When we add a suffix that starts with a vowel to a word ending <e>, we usually drop the <e> and add the suffix. At that point, I would model on the board underneath the word sum so that students can see the relationship between the sum and the completed word.

I would then say the base word, please, with the suffix <ed>. Base word, please, with the suffix <ed> and have the students repeat that. Get a little song going. It really will help them. Then I would say drop the <e> and add the suffix and have students repeat that and tell their partners. Base word, please, with the suffix <ed>. Drop the <e> and add the suffix. No, it doesn't rhyme, and that's okay. Depending on the age of the students, how much time I had and what the purpose of the lesson was, I might rub it all off and have the students construct the word themselves, and if it was a spelling lesson, I'd give more examples for the students to spell. If the focus of the lesson was vocabulary, I wouldn't do that last bit. My personal view is that there is nothing inherently wrong with putting the dots and dashes into the whole word, pleased, but that it's a missed opportunity if we don't go to that next step and explain the morphological aspect of the word as well. This work can be done across the curriculum. Anytime you encounter a word that the children need to be able to read or write, you can provide these explanations, and in doing so across the curriculum, you will help them learn to generalize these rules.

00:18:08

Question 3 - Monitoring Progress.

Our final question comes from Kathleen J. She asks,

I'm struggling to monitor progress regularly in my year one class. What tips do you have to make that work? Where do you snatch the time to do it? I have a TA until the second break, Monday to Thursday. I have tried having kids record their decoding to listen to later and doing group dictation to mark after class, but the listening never gets done thoroughly after class due to family life, and I don't get to give good feedback, so this model isn't working. How can I tweak it to make it work? What else can I try?

To help Kathleen out, I called on Nadine, who's been part of my world for a number of years now and is a gifted teacher. She has a particular system for feedback on reading that has gotten her great results. Nadine says, "I agree that it can be very difficult to monitor progress regularly with all of the stumbling blocks you listed. What I found worked really well for me was scheduling over the week when I worked with children and whatever feedback they would receive for reading and writing. The children with the greatest learning needs received feedback in smaller chunks more often. For reading, I have five reading groups and the children with the greatest needs read with me more often. I start with partner reading, and during that time, I read with a group of children". So what Nadine's saying is that all of her children have partner reading opportunities, whole class, everyone's reading with a partner, but during that time, she draws out a small group to work within that time. "After partner reading, some children draw a picture to match the text they read, some record themselves reading on the app that the school uses for parent communication, and another group reads with me". So that's a second group. So Nadine listens to one small group, and then another small group comes to her while students do a follow-up task. "At night, I choose two to three children who record themselves on the app and give them feedback". Now Kathleen's already said that that's really tricky for her, and Nadine was just sharing what she has been able to make happen. "At my school", Nadine says, "PM benchmarking is required to be completed at the end of each term, and I do this over a week. The whole system really works well for me because I have very robust routines, transitions, and expectations in my classroom. It takes a little bit of work to get this up and running, but it's really worth it. I feel that I'm able to monitor progress and provide quality feedback to children".

I think the important thing to remember here is that it's not one size fits all for every school. Each school will have its own contextual challenges. The students will have a number of needs, and in her question, Kathleen described that she has a number of children with learning difficulties, huge social and emotional needs, and requirements from the school to be doing things that maybe are not that effective and just finding herself being really tired at the end of the day. That's why, for Kathleen, feedback after the fact isn't really working because, by the end of the school day, she's just spent, and you know what? I get that completely.

I like Nadine's idea about utilising the partner reading time. Now for Kathleen, having a classroom assistant means Kathleen could be taking a small group, and the classroom assistant can keep everyone else on track because there are just some kids who need a grownup hovering around to make sure that they stay on task. Then when they switch groups for the follow-up task, the classroom assistant can keep doing that. But in your classroom, if it was possible, you might have your classroom assistant also take a small group. Yes, that's not you listening to them, but they will at least be having a grownup. The other thing that I want to say as well is that you can utilize other times in the day, like after lunchtime. So yes, the children are going to come in all tired and sweaty after lunch, and they'll grab a nonfiction book and, you know, park themselves under a table somewhere and have a read and that's good relaxation time. You can provide additional listening time during that by taking a small group yourself so that you're able to check in with those students who need more help more often.

I have no magic ideas, everyone, for how you fit everything in. What I do know is that every small thing you do that moves your classroom closer to one where structured literacy is the norm is a real gift to your students. In terms of monitoring, you can also use things like exit tickets. So you can say, today, I really want to check in on these three students with some phonics or phonemic awareness or whatever it happens to be. Everyone gets an exit ticket, but you're paying particular attention to those few students, and then over a week or two, you're able to tick off. You don't have to find time to make sure that everyone else is sitting nicely while you pull the children aside one at a time.

The more complex the context, the simpler everything else needs to be. So everybody and Kathleen, please give yourself some grace to celebrate the wonderful things that are already happening in your classroom. We can feel like the mountain is so high and that we're never going to get there, that if we can't do all of the things, then we're not good teachers. That's just not the case. Do what you can with the time and the resources (which is usually about people) that you have available to you, and you're not going to break the children. It's going to be okay.

I just want to give a few extra notes about Nadine's response. The thing that I take away from Nadine's response here is that she's demonstrating that small group work doesn't have to be banished from the classroom. She sees two groups per day for about 10 minutes each. While she's working with small groups, the other children aren't playing useless games or doing collage. They're reading with a partner or doing a follow-up task. Students who need more help are seen more frequently. Feedback is both immediate and personal. Nadine will be the first to tell you that it does take a concerted effort to make all of this happen, and as you heard from her response, it does take work to establish routines and expectations, but the payoffs have been enormous for her students.

00:24:11

Do you have questions about Structured Literacy?

If you have questions about any area of literacy instruction and are a member of the On the Structured Literacy Bus Facebook group, be sure to pop them into an Ask Anything post that is shared each Monday. Don't wait until Monday to ask. Just find one of the posts and go for it and if you're a current member and someone asks a question that you have a solution to, please feel free to pop in there and share your wisdom and experience with others. If you aren't a member of the group, why not join us, but be sure to answer all the questions when you request to join. This is showing that you're willing and ready to engage. We might not be the biggest group on the internet, but I'm okay with that. Our bus drivers are dedicated, curious, and positive in their approach. There are no snarky comments, no need to say, "Please be kind." when asking a question. Everyone is just kind. We support each other and work our way through the busy world of structured literacy.

I hope that you found value in listening to the questions of others today and the answers that go with them. Have a marvellous day, everyone. I'll see you next time. Bye

References

Dehaene, S. (2009). Reading in the brain: The new science of how we read. Penguin Books.

Ehri, L. C. (2014). Orthographic mapping in the acquisition of sight word reading, spelling memory, and vocabulary learning. Scientific Studies of Reading, 18(1), 5–21. doi:10.1080/10888438.2013.819356.

Seamer. J. (2022) Reading Success in the Early Primary Years: a Teacher's Guide to Implementing Systematic Instruction. Routledge.

Would you like a simple outline of the research evidence of Structured Literacy AND detailed guidance for how to bring it to life? Order a copy of Reading Success in the Early Primary Years here.

Jocelyn Seamer Education

Jocelyn Seamer Education

2 comments

Another fantastic podcast Jocelyn. The way you break complex concepts down into plainly worded and easy to understand chunks is fantastic. Thanks for everything you and your team do. I appreciate the understanding, patient, kind attitude you have towards teachers, who we know constantly have so much on their plates. Thanks :)

Leave a comment