The Joy and Terror of Teaching in the First Year of School

I remember my very first year teaching foundation (depending on where you live it is known as kindergarten, pre-primary, reception, prep or transition). I was handed some keys, given a class list and told to get in touch if I had any trouble. Trouble? Boy, did I have some trouble. I was lucky enough to have some great professional learning in a range of areas in that first year which set me on the path to effective teaching, but I certainly had my moments of ‘what am I even doing here?’ and ‘I must be crazy!’. This post is dedicated to those brave souls who are teaching the first year of school in 2021. Whether you are new to teaching, new to teaching foundation or a veteran of this age group, I would like to share some of my learnings from my time on this most-important grade. Incidentally, these learnings are relevant to year 1 and 2 as well, so please keep reading even if you aren’t a foundation teacher!

Learning 1 – 5 year olds are not small 10 year olds

I first heard this when I had the opportunity hear Kathy Walker (the founder of Walker Learning) speak. It was like a bell went off inside my head as I came to a new understanding of my role as a teacher. I realised then, that my role wasn’t just to teach reading and maths (although it certainly was an important part), but my primary role was to respond to the needs of the little people in front of me. I was teaching in a remote Aboriginal school at the time. One where children came to school speaking very limited English, had little exposure to books, conversation or spending time sitting quietly, paying attention to something that wasn’t a device or the television. Now, these conditions are not exclusive to Aboriginal Communities and the lessons I learned in that school have stood me in good stead regardless of the context in which I have found myself teaching.

5 year olds have a special set of developmental needs. My first task was to support the children to learn to do things I thought were pretty basic, like sit on the mat to listen to a story, follow an instruction, negotiate with another child if they both wanted something and learn to just ‘be’ in the classroom. My judgement of what I thought they ‘should’ be able to do had no place in that classroom. My job was to meet the children where they were and walk them gently to their next steps.

The major implications of 5 year olds not being small 10 year olds are:

- Children will have an attention span much shorter than you would like. Forget 30 minute lessons on the mat. Go for 10 and work up from there.

- Children are still pretty egocentric at this age and aren’t necessarily ready to see things from another person’s point of view. They will likely need support to negotiate with their peers.

- Giving longwinded instructions with multiple parts will result in children wandering all over your classroom like chickens. Keep instructions short and use visuals.

- If you don’t take the time to help children interpret your instructions most will forget what you just asked them to do between where you are standing and 3 metres away

- Changes in routine can, and will, result in chaos. Keep daily routines consistent and provide visuals for your day that you remove as you complete each item.

- Tasks will take a very short amount of time for children to complete meaning that the 30 minute task you had planned will be done in about 8 minutes.

- Not all children can get themselves to the toilet on time

- Sitting and listening is not a great strength of 5 year olds. Give them lots of opportunity to use all of their senses and include action and movement wherever possible.

There are many other implications for teaching this age group. You can find a handy downloadable at https://www.responsiveclassroom.org/sites/default/files/ETKintro.pdf

Learning 2 - Language development doesn’t ‘just happen’.

It is really easy to take for granted that children’s language development occurs naturally, and for most children it does. However the exposure that children have had to a range of rich vocabulary through conversations, books and experiences is likely to vary widely amongst your students. All reading floats on a sea of oral language (yes, I have ‘borrowed’ that). If children do not have a well-established oral vocabulary and ability to understand what is said to them when they arrive at school, they are already behind. In order to support all children’s language development in preparation for reading and writing, your classroom must be a language rich one. Here are some of the features of a language rich classroom:

|

· Teachers plan for student opportunities for talk as well as listen. This is visible in teacher planning. |

|

· Teachers carefully select texts to read the class for enjoyment that contain rich and varied vocabulary and concepts. These vocabulary and concepts are unpacked so that all children can understand what has happened in the story. |

|

· Students know the engagement norms for classroom discussion and follow them with minimal prompting (sitting knee to knee with a partner, conversation turn taking). |

|

· Teaching uses a gradual release of responsibility model (I do, We do, You do) to frame oral language development. |

|

· Students have opportunity for meaningful talk in play based and hands-on experiences such as dramatic play and conducting interviews. |

|

· Rich texts are used as the model for intentional and explicit teaching of language structures and vocabulary. |

|

· Language development is a focus across all areas of the curriculum |

|

· Hands on activities are provided for students to retell familiar stories (puppets, cut outs etc) |

|

· Class discussions happen where children talk about settings and characters in stories. |

|

· Teachers explain the multiple meanings of words. E.g., bat can mean an animal, a piece of sports equipment or the action of swiping something away with your hand. |

You can learn more about creating a language rich classroom and other characteristics of responsive and developmentally appropriate practice at https://earlychildhood.qld.gov.au/early-years/age-appropriate-pedagogies/characteristics/language-rich-and-dialogic

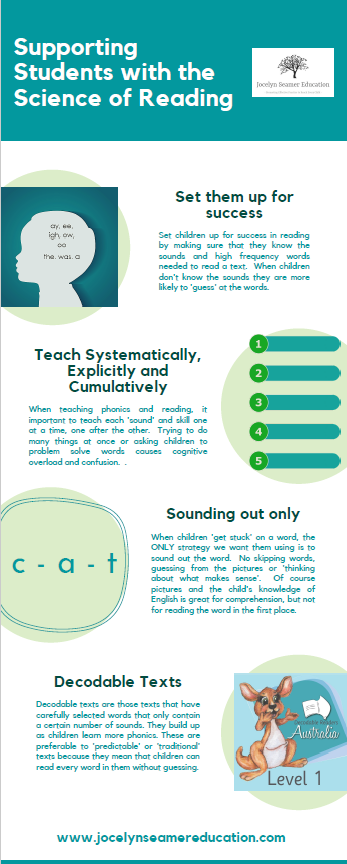

Learning 3 – The form of reading instruction you provide matters. A lot.

When I entered my first foundation classroom I already knew that phonics was an important part of teaching reading. I also knew that it had to be taught explicitly and sequentially. What I didn’t know, was that what that really looked like. I thought I knew, but I didn’t. Luckily, there were those who did know and I was so very fortunate to be introduced to sound, evidence based practices in reading instruction before I did too many children too much harm. I have since then developed a love of implementing the Science of Reading and have seen the transformative effects of bringing all 5 areas of reading instruction (phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary, fluency, comprehension) to the classroom in an evidence-based way.

Despite claims to the contrary, there is one best way to teaching reading so that we reach as many students as humanly possible, including those with dyslexia and other learning difficulties. We don’t have to choose who to serve in our classrooms. Just teach every child as if they were dyslexic and every child will benefit.

There are 8 key actions of evidence-based reading instruction:

Key action 1 - Intentionally teach oral language concepts and skills.

Key action 2 - Explicitly build vocabulary and background knowledge

Key action 3 - Explicitly teach phonological and phonemic skills

Key action 4 - Teach phonics systematically and explicitly

Key action 5 - Teach phonics using a set sequence

Key action 6 - Closely monitor progress and reteach as needed

Key action 7 - Teach blending and segmenting together

Key action 8 - Provide decodable texts that align with your phonics progression

Teaching the first year of school IS filled with joy and terror. Joy when you see the burgeoning skills coming to life. Joy when a child yells out, “I can do it!”. It is also filled with terror, because the implications of getting this year ‘wrong’ are serious. Children who end the first year of school without the fundamental skills in reading and writing are likely to end up as struggling or failing readers in year 4. Statistically, those who start behind will stay behind.

But this terror can be overcome by finding those people around you who have been there before you, made the mistakes and lived to tell the tale.

You can also download my free teaching guide 'How to Teach Reading in the First Year of School' below.

0 comments

Leave a comment